Our focus is identifying attractive investment opportunities in developing markets to reduce carbon emissions and generate compelling returns.

Mind the Gap

Ahead of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, there is a widening gap between global ambitions to accelerate action to tackle the climate crisis and the reality of transition challenges facing many developing markets. Several developing countries share the long-term goal to reduce emissions. However, they face challenges financing the transition, guaranteeing energy security, and mitigating the social-economic impact of phasing out fossil fuels. A concerted approach to bridge this climate action gap is at the crux of staving off the worst effects of global warming.

At Olduvai Capital, we help bridge the climate funding gap by identifying attractive investment opportunities to reduce global carbon emissions and generate compelling returns.

Emissions of the Future are in the Developing World

Achieving the goal of limiting global warming to below 1.5°C will be won or lost in emerging markets. Over the last 20 years, emerging markets with a fast-growing population and rising energy demand have fueled their growth by burning more carbon-intensive fossil fuels. On the other hand, developed markets have gradually reduced their carbon footprint by transitioning to a less carbon-intensive energy mix.

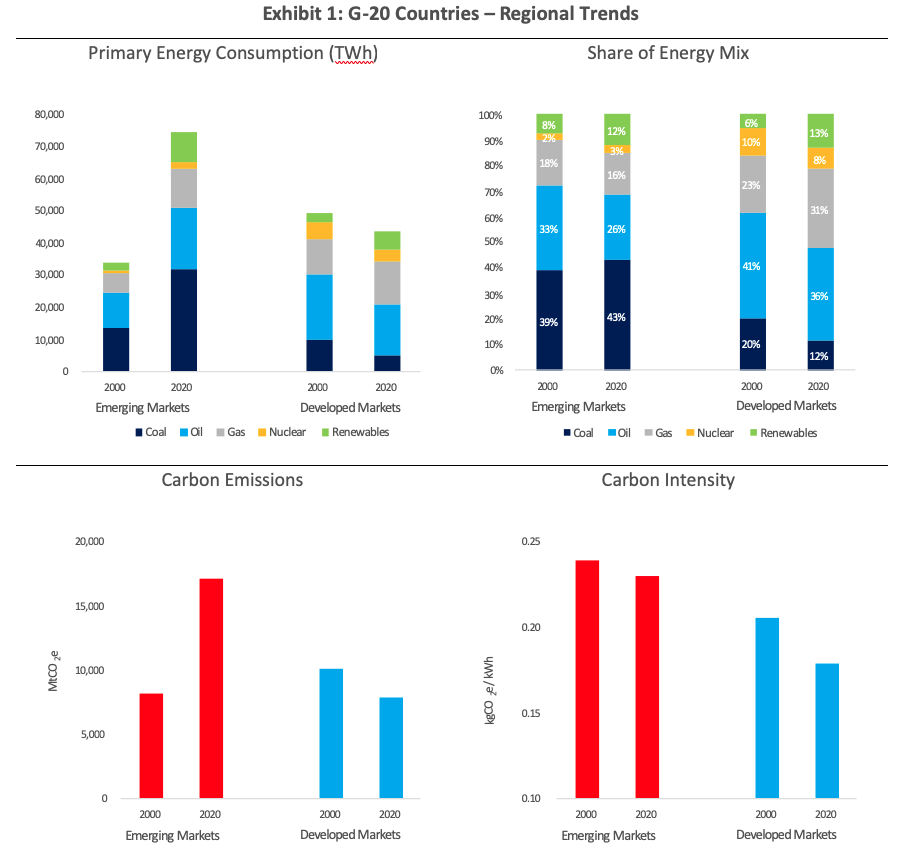

These regional disparities are illustrated in Exhibit 1, comparing the energy consumption and carbon footprint in the G-20 countries, representing the world’s major economies and nearly 80% of global emissions. Since 2000, total energy consumption in G-20 emerging markets has grown at a 4.2% CAGR, compared to a steady decline of 0.6% in G-20 developed markets. Coal’s share in the energy mix has increased to four times higher in emerging markets compared to developed markets. Consequently, over the last 20 years, the carbon footprint in emerging markets has grown at a 3.8% CAGR but reduced by 1.3% CAGR in developed markets. Over the same period, the carbon intensity of energy production, measured as the amount of carbon emitted per unit of energy, has dropped by 12.9% in developed markets compared to a 3.9% drop in emerging markets. In short, developed markets have decarbonized their energy systems over 3x faster than emerging economies. Accelerating the pace of decarbonization in the developing world is central to tackling the climate crisis.

With rising energy demand, emerging markets are burning more carbon-intensive fossil fuels, while developed markets are transitioning to a less carbon-intensive energy mix.

Among the G-20 countries, developed markets have decarbonized their energy systems over 3x faster than emerging economies.

Our focus is identifying attractive investment opportunities in developing markets to reduce carbon emissions and generate compelling returns.

Obstacles to Decarbonization in Developing Markets

For many developing countries, the challenges for not acting fast enough revolve around three core points:

- Mobilizing private capital to finance the energy transition

- Guaranteeing energy security to ensure reliable and affordable energy access

- Mitigating the social-economic impact of phasing out coal

Scaling up private sector investments in developing countries is crucial to ensure equitable access to clean energy by the end of this decade. Using Africa as an example, according to the U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, the continent’s current installed energy capacity of 250 gigawatts (GW) needs to double by 2030 and increase fivefold by 2050 to meet rising energy demand and requires investments of over US$500 billion. Mobilizing substantive private sector investments is critical given the limited fiscal space in most developing countries.

Energy security entails timely investments to accelerate the transition to cleaner energy sources while ensuring resiliency to sudden changes in the supply-demand balance. Recent price volatility in energy markets and higher levels of supply variability underscore the energy security risks that could undermine public support for the energy transition in developing markets. There is broad consensus on ditching new coal-fired power plants but divergence on the pace of phasing out existing coal assets. Natural gas supplies a growing share of energy demand in many developed markets (United States 34%, Europe 25%), but it is less prevalent in energy-hungry emerging markets (China 8%, India 7%, South Africa 3%). Critics argue that although gas is less carbon-intensive than coal, it is not carbon neutral and emits methane. Proponents view defunding gas projects as inequitable, arguing for lower-carbon generation sources to keep up with rising electricity demand and reduce the energy poverty gap. A pragmatic approach would ensure meeting energy demand with low carbon intensity while still scaling renewables – the path taken by developed markets.

The social-economic argument is pertinent to potential job losses and wider economic repercussions in coal-reliant countries. Reflecting the political sensitivities in many coal-reliant countries, leaders of the G-20 countries have resisted making a collective commitment to accelerate the phase-out of coal ahead of COP26. Managing social-economic impacts and the concept of a ‘just transition’ is not new. The European Union has recently capitalized a US$20 billion Just Transition Fund to support economic diversification and assist affected areas and workers. Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries committed to providing US$100 billion per year to finance transitions in emerging markets, but the pledges have not been met.

South Africa: Opportunity Amidst Challenges

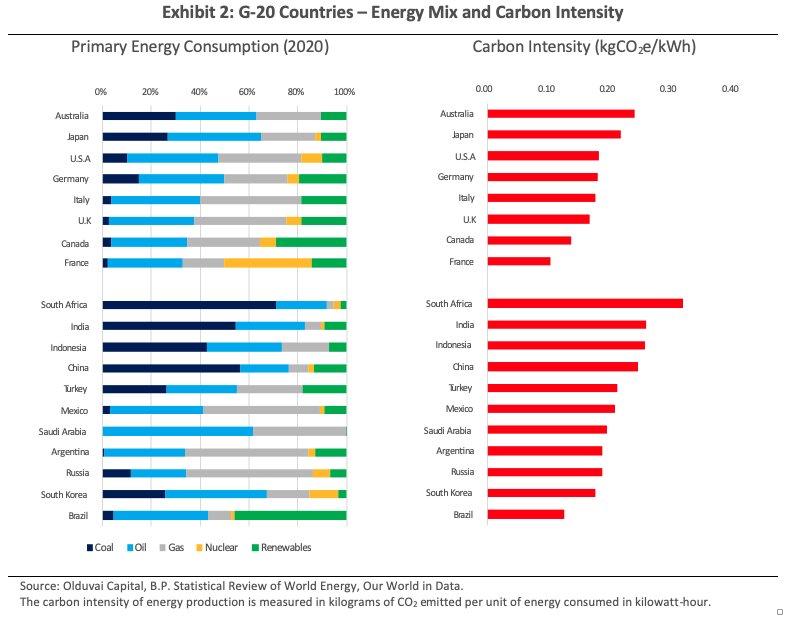

Among the G-20 countries (Exhibit 2), South Africa stands out with the highest carbon intensity driven by a 71% share of coal in its energy consumption mix, the highest worldwide.

Africa's most industrialized country has the highest carbon intensity among the world's major economies.

High carbon intensity is a risk to the export competitiveness of developing markets, considering the potential introduction of carbon border taxes and global consumers increasingly seeking carbon neutrality.

Limited fiscal space in most developing countries constrains funding for climate change solutions, while donor funding is simply not enough. Scaling private sector capital is the only feasible solution to finance the energy transition in developing markets.

Africa’s most industrialized country illustrates the opportunity to tackle the climate crisis but exemplifies many challenges facing developing countries. For starters, there is a national interest in reducing emissions. The government has highlighted that South Africa’s high carbon intensity is a threat to the competitiveness of the country’s exports, considering the potential introduction of carbon border taxes and global consumers increasingly seeking carbon neutrality.

South Africa’s strong imperative to accelerate the transition to renewable energy sources is matched by the abundant potential of its solar and wind resources. Eskom, the monopoly state-owned power utility, estimates that the cost competitiveness of renewables outpaces that of alternative energy sources (solar = 4.1, wind = 5.4, gas = 7.3, coal = 15.9 in US$c/kWh). Further signaling its ambitions, Eskom has shelved new coal-fired power plants, announced plans to decommission existing plants over time, and identified investments in renewables and gas to support the transition.

However, South Africa is facing a stark gap between its energy transition ambitions and reality. The country’s energy supply-demand balance has worsened over the years, and existing generation capacity is inadequate to meet current demand, necessitating incessant power rationing and hampering economic growth prospects. The energy availability of Eskom’s power stations has declined from above 90% in the early 2000s to 64% in 2021, reflecting an aging fleet of coal-fired power plants with an average age of over 41 years old, excluding two recently commissioned plants. The company plans to decommission 22GW of coal-fired capacity by 2035. Further, the current generation capacity shortfall is estimated at 4GW to 8GW.

All in all, an estimated 33GW of new power generating capacity needs to be added and would require over US$68 billion in new investment. In addition, significant investment will also be necessary to upgrade the country’s aging grid infrastructure to connect new generation capacity.

Conclusion

Accelerating the pace of decarbonization in developing markets is central to limiting global warming to below the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement. Most developing countries share this global ambition but face challenges financing the transition, guaranteeing energy security, and mitigating the social-economic impacts. Bridging this climate action gap requires the collective efforts of policymakers, public finance, development finance institutions, and the private sector.

At Olduvai Capital, we aim to generate sustainable long-term returns. We have often found attractive opportunities when investors overweight near-term risk factors in developing markets at the expense of longer-term structural trends that take time to play out. Financing the multi-decade energy transition in fast-growing economies with sizeable unmet energy needs offers an emerging opportunity to reduce carbon emissions and generate compelling returns.